I have always loved drawing. Up until the age eight, I thought I was quite good at it. At that point, I began to realise that the world sees us as those who “can draw” and the rest who can’t. This is nonsense. As children we explore, express and try to understand our world through the pictures that we draw, well before we can do that with words. So how come the words carry on doing the work and we leave the drawing behind? Because someone made us think we could not draw.

When I was at primary school, my class visited a local museum. My class stopped in front of a case displaying a fossilised hippopotamus tooth. The teacher said that she needed someone who “could draw”, and picked out our very own prodigy, a girl whose talent at drawing had already made her something of a celebrity. She duly stepped to the front with her notebook and began a painstakingly beautiful pencil rendition of said fossil. The class looked on in awe. Disgruntled, I began sketching the tooth in my own book. It wasn’t anything like as good as hers, and my teacher was less than impressed with my lack of respect and admiration. However, all these years later, I have remembered that fossil. I remember it because I drew it.

Much wonderful work has been done looking at dual coding – the way that words and images work together as part of the learning process. A great place to start for those interested in pursuing the theory is this Learning Scientists blog, or @olivercavigliol’s twitter feed. I’ve only recently started reading around the theory – but I have known for a long time that using drawings and other images helps learning.

However, it is only recently that I have brought my own drawing into my teaching of poetry. I doodled in meetings; I occasionally took a sketch pad on holiday – but I did very little more. One half term, I did a small drawing of things I wouldn’t want to be without:

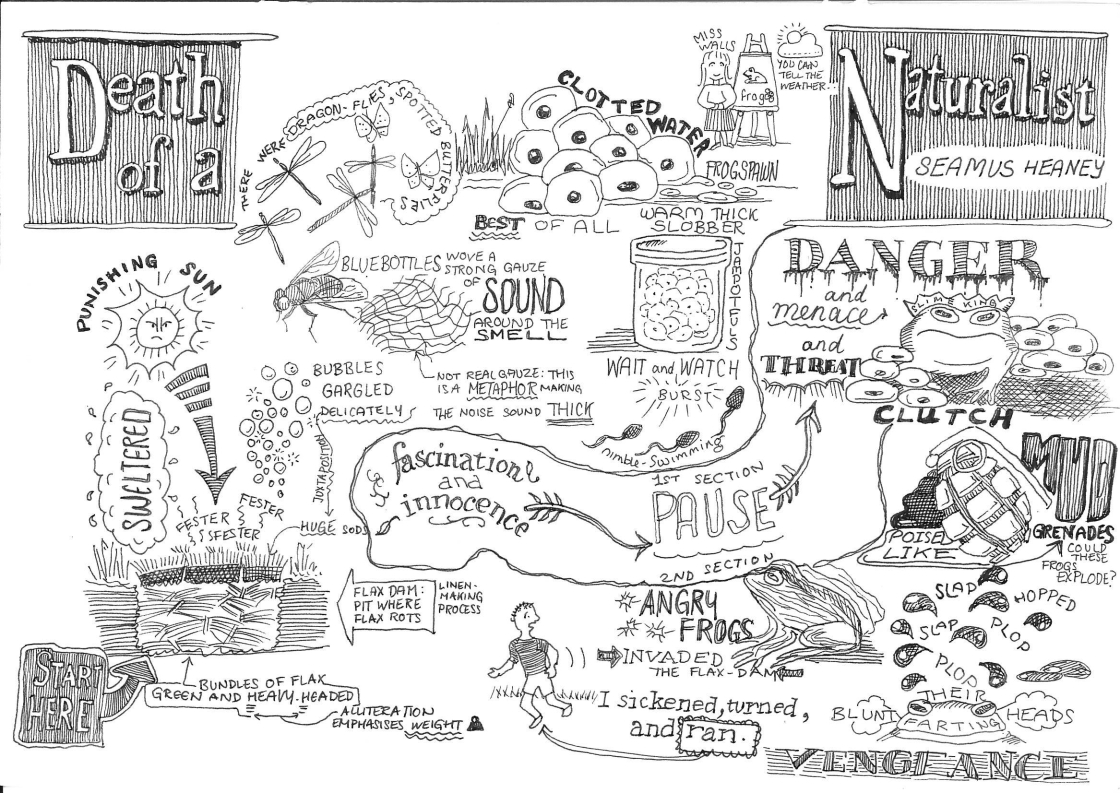

I enjoyed doing it; I went back to school and forgot all about it. However, I soon found myself about to teach Seamus Heaney’s “Death of a Naturalist” yet again. I’ve lost count of the number of times I’ve taught that poem but, to my shame, I’d never researched what a “flax dam” was. I looked it up. I drew a picture – as much for my own understanding as for my students – and then I just kept going:

What made this so different from my previous efforts to use image in my teaching was that I was engaging more in the learning myself. Creating the drawing took me into the poem in a new way. I found it helped me understand the structure better, and see more of the shape of the poem. It was also great fun. I have always loved typography, and found that I was selecting significant words, then choosing a style for them that felt appropriate. I shared the drawing with my class, who loved it. It seemed I was onto something.

Since then, I have kept on drawing, and I kept on trying not to worry when things did not look quite like I intended them to. More importantly, I have worked hard to encourage my students to join in. I was delighted by this, from a Year 10 student: A bun, dancing. We were off. The next step was to pay some close visual attention to metaphor. Here’s an example:

A bun, dancing. We were off. The next step was to pay some close visual attention to metaphor. Here’s an example:

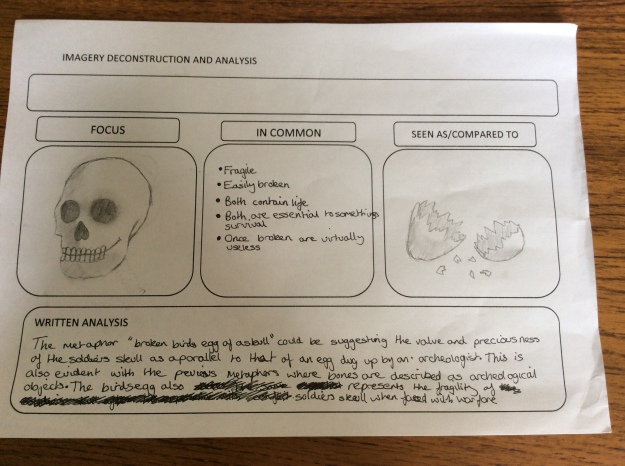

For this student, the drawing definitely helped them to articulate their thoughts – the process of drawing helped the thinking. It is exploratory – the student later rejected the idea of the archaeologist, having realised that they would be unlikely to excavate birds’ eggs (!), but used the concept of fragility in some later, powerfully developed writing.

For this student, the drawing definitely helped them to articulate their thoughts – the process of drawing helped the thinking. It is exploratory – the student later rejected the idea of the archaeologist, having realised that they would be unlikely to excavate birds’ eggs (!), but used the concept of fragility in some later, powerfully developed writing.

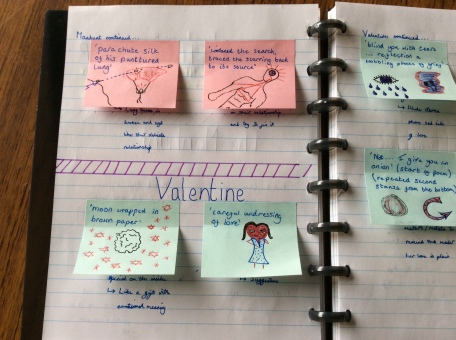

For another student, using small drawings has transformed his revision notes:

His written notes sit underneath the post-its so that he can quiz himself using the images as prompts. I think it’s brilliant.

His written notes sit underneath the post-its so that he can quiz himself using the images as prompts. I think it’s brilliant.

I have since tackled more of the poems from the Eduqas Anthology. Toughest so far has been Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s “Sonnet 43”; such a cerebral text, it defies interpretation through drawing. However, that very discovery led me deeper into the ideas. The images for the poem, when I used them with my class, became talking points, possibilities. We were able to engage with the abstract, elusive nature of her language as I explained how impossible some of the phrases were to draw – the sheer difficulty of matching images was a great starting point for discussion.

Since then, some Staves from A Christmas Carol, and most recently, Macbeth.

You can find the drawings at All the Drawings so Far

I’ll finish with a very big thank you to the lovely people at Eduqas, NATE 2017 and TL Leeds 2017 who have enabled me to share some of what I am working on.